Why “difficult employees” are a leadership diagnostic, not a task

One of the most important lessons we learned from Ron Heifetz at Harvard Kennedy School is that leadership is not about authority - it is about diagnosing and intervening in complex human systems. Nowhere does that become clearer than when you are dealing with a difficult employee.

Traditional leadership paradigms teach us to zoom in on the problem. Rooted in classical management and Taylorism, they locate the problem with the individual. Someone underperforms or disrupts the team, so you correct them through training, incentives, or personal development.

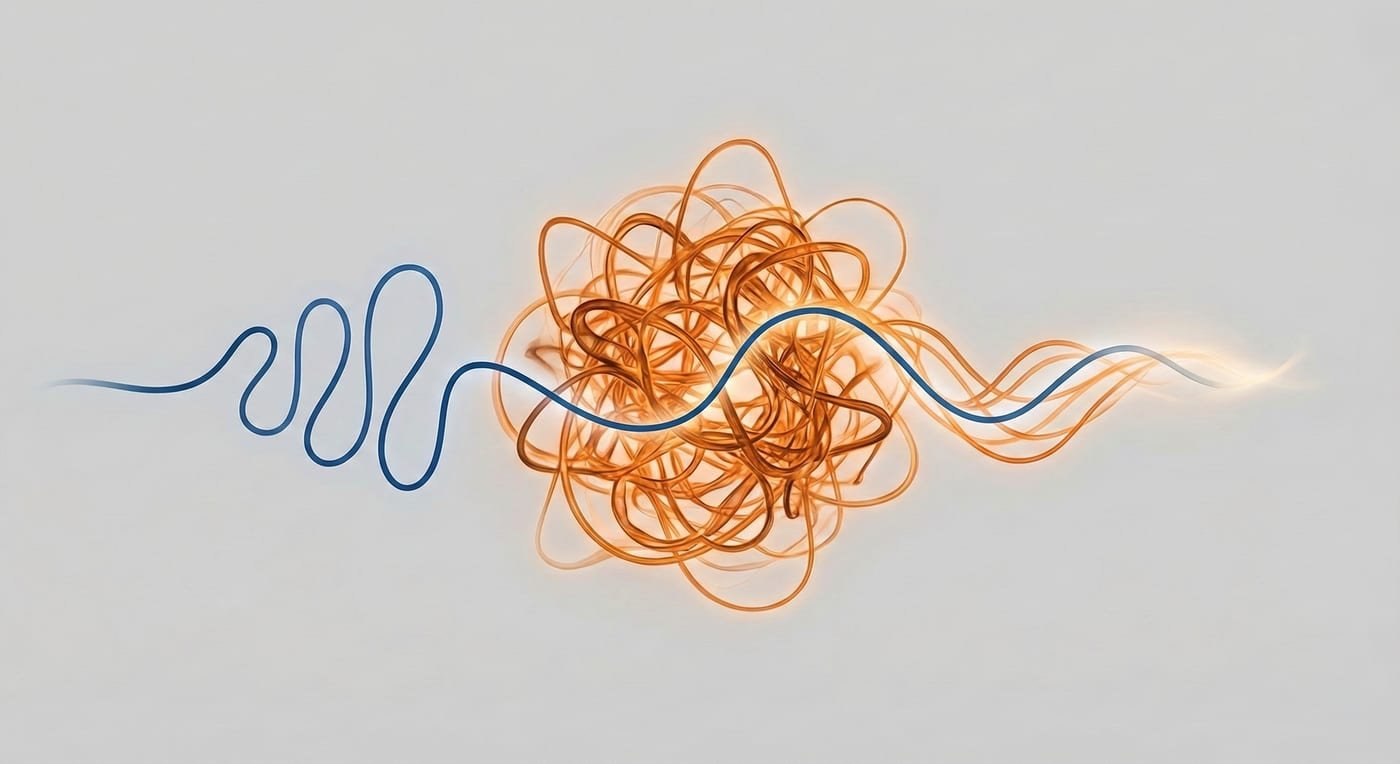

Adaptive leadership takes a more systemic approach. It zooms out. It reframes the challenge within the system, not the person, looking beyond the individual to understand the context shaping their actions.

Difficult employees are not a simple task on your list. They are an adaptive challenge, one that tests your judgment, your ability to separate role from self, and your willingness to have conversations most people avoid.

And yet, if you search “how to deal with a difficult employee,” you will find page after page of generic advice: give feedback, have a conversation, set expectations. These articles speak to a broad audience of managers, but not to senior leaders who bear legal risk, cultural responsibility, and organizational accountability.

Here is a 5-step SOP for handling difficult employees that holds the system to account, not just the individual.

Before acting, ask yourself: what am I assuming about why this employee seems difficult?

- Is this a skill gap?

- A misalignment with expectations?

- A symptom of broader team dynamics?

- A reflection of systemic pressures?

What lens am I bringing to this situation? What expectations, assumptions, or unspoken standards might I be applying here? Have I felt this way with others, or is something unique surfacing?

Misdiagnosis is the single greatest cause of escalation or disengagement when dealing with a challenging employee or team dynamic.

Technical problems have clear solutions. A missing skill can be taught, a process can be fixed, a rule can be enforced. Adaptive challenges are rooted in people, culture, and systemic dynamics. They have no pre-packaged solution. You have to learn your way into a solution. Most difficult employee challenges are adaptive.

Behavior rarely exists in isolation. To lead adaptively, look beyond the individual to the system that shapes them. Ask:

- How do formal structures, incentives, and informal networks shape what people do, and what they feel safe doing?

- Are team norms or peer expectations reinforcing damaging behaviors?

- What systemic tensions or conflicting pressures might be influencing performance?

- How am I contributing to the dynamic?

- What history exists that explains the situation?

Where might expectations be unclear or misaligned? Could the behavior be adaptive to pressures I have not fully understood? Are there hidden norms or legacy dynamics at play?

Zooming out helps you design interventions that address root causes and anticipate unintended consequences.

To make progress you will need to intervene on two levels, directly with the employee and more systemically. The starting point is curiosity. Have one or multiple conversations with the employee to find out more. What are you assuming they know about what you expect? What are they assuming you understand about their situation or why they are acting as they are?

You are not having a “problem employee” conversation. You are having a conversation about communication, alignment, expectations, assumptions.

- Name the situation precisely. No exaggeration, no judgment. As the Crucial Conversations methodology puts it, separate the facts from your story about the facts.

- Explain the impact. How does this behavior affect team culture, decision making, and their own goals?

- Invite perspective. Ask questions that surface underlying motivations or pressures. How do they see the challenge?

- Co-create next steps. At some stage, though likely not the first conversation, once you have made it clear that you are genuine about wanting to improve the situation and the employee can see that change is needed, agree on experiments or checkpoints that allow learning and accountability.

To succeed here, leaders must hold the heat, navigate tension without collapsing, and balance accountability with support.

What can I do to ensure this feels like a real invitation, not a trap? Am I creating space for them to stay in the work rather than retreat or resist? Is my tone reinforcing alignment, or unintentionally creating distance?

Unless you are very lucky, the challenge does not live entirely in the difficult employee. They are a product of the system. You will need to go beyond having difficult conversations to find out more about what needs to change. Use interventions as ways to probe the challenge, not to solve it in one move.

- Shift structures. Change roles, responsibilities, or reporting lines to surface hidden tensions.

- Create peer engagement. Not to correct the individual, but to surface new perspectives and reveal patterns.

- Adjust incentives or norms. Look at what may be enabling problematic behavior and watch how the system responds when you change it.

- Observe and iterate. Notice what resists, what adapts, and what signals deeper challenges.

Your goal is learning, not control.

Who else in the system might help illuminate this? What invisible norms or peer pressures might need surfacing? Have I been too focused on solving this alone when the system needs to shift?

After each intervention, pause and ask:

- Has the behavior shifted? Why or why not?

- Are team dynamics improving, or are new tensions emerging?

- What patterns are now visible that were hidden before?

Every cycle of diagnosis, conversation, and intervention informs the next.

This approach keeps diagnosis at the center, avoids HR heavy tools like performance improvement plans, and emphasizes experimentation and iteration. It is a repeatable process for senior leaders facing challenges that do not have easy answers.

If nothing shifts, what then? Could the most honest, adaptive move be to help this person find a better fit elsewhere? Am I clear on when continued engagement is productive, and when it is not?

Putting the 5 steps into practice

Use this guide in real time with a specific employee in mind. Work through each step explicitly rather than jumping straight to a performance conversation.

- Step 1. Write down your first three assumptions about why this person is difficult. Then, next to each one, note whether it describes a technical issue or an adaptive one.

- Step 2. Map the system around them. List the incentives, norms, and relationships that shape what feels safe or risky for them.

- Step 3. Draft three questions you can ask in your next conversation that surface assumptions on both sides.

- Step 4. Identify one small, safe to try systemic experiment (a shift in structure, process, or peer engagement) and note what you will watch for.

- Step 5. Schedule a short reflection with yourself two to three weeks later to review what changed and what did not.

Over time, this practice turns “dealing with a difficult employee” from a dreaded task into a disciplined way of reading and reshaping your system.

One page reference for quick use

| Step | Key questions | Embedded leadership prompts |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Diagnose the technical and the adaptive | Is this a skill gap, expectation misalignment, team dynamic, or systemic pressure? | What assumptions am I making? What expectations are being violated - mine or shared ones? |

| Step 2: Zoom out to understand the system | How do structures, incentives, norms, and networks shape this behavior? What history or dynamics might be influencing it? | How might I be contributing to this? What am I not seeing about the system this person operates in? |

| Step 3: Hold multiple difficult conversations | What are they assuming I know? What do I think they know? Are we aligned? | Am I holding the heat or avoiding it? Am I fostering learning or defensiveness? |

| Step 4: Experiment and intervene systemically | What structural, peer, or incentive shifts might reveal more? What happens when I adjust something? | What changes? What resists? What experiments feel safe to try but high learning? |

| Step 5: Reflect, iterate, return to diagnosis | What shifted? What stayed the same? Are we closer to clarity or resolution? | Am I clear on whether this is a fixable challenge, or one that requires a deeper decision? |