While preparing the new leadership core course at Columbia SIPA, I found myself returning to the Chilean mine collapse of 2010 - a crisis that still holds sharp lessons for leadership under pressure.

Thirty-three miners were trapped more than 2,300 feet underground after a catastrophic cave-in. When the Minister of Mining arrived on site more than ten hours later, he found chaos: no clear leadership, families in upheaval, no plan in motion.

It was a haunting scene: lives potentially lost, no clear plan - and no one visibly in charge.

This kind of crisis belongs to a specific, often overlooked category - where both uncertainty and urgency are high, and conventional leadership tools may falter. It took 17 days to discover the miners were alive, thanks to a narrow borehole that reached their emergency refuge deep underground - marking the deepest rescue ever managed.

The Leadership Challenge Map

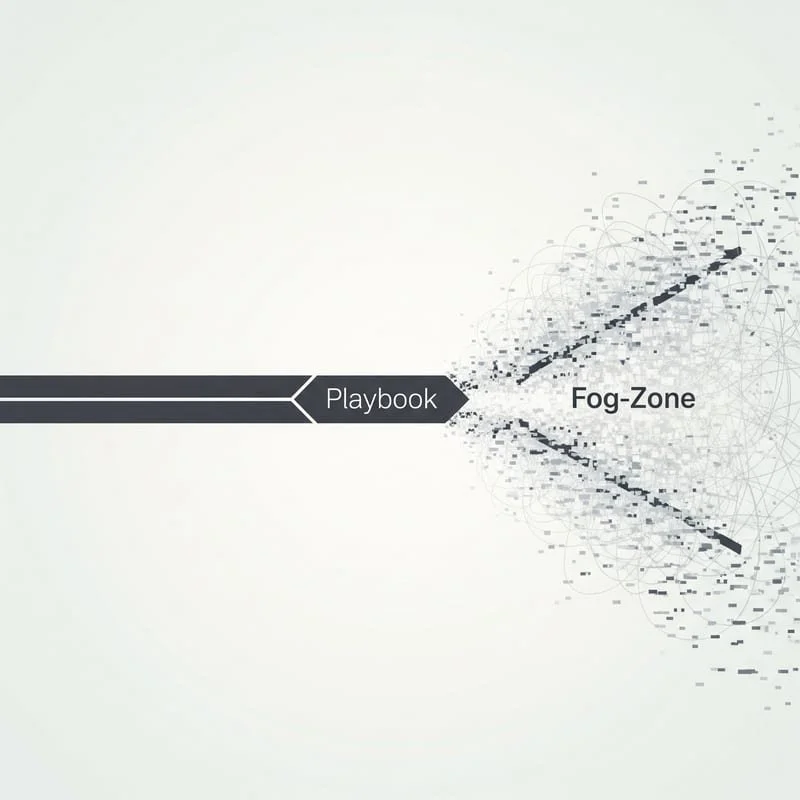

If we map leadership challenges on two axes - uncertainty and urgency - the Chilean mine crisis falls in the top-right quadrant: high-stakes, high-ambiguity. And it demands a different kind of leadership logic. Here are the quadrants:

Expert Delivery (deliberate speed, low uncertainty): Complex but predictable work that depends on coordination and expertise. Think airport construction, complex software implementation, or onboarding a new employee. Known problem, proven solution.

Expert Response (high urgency, low uncertainty): These are crises with known solutions - emergency surgery, firefighting, a cybersecurity breach. Action must be swift, and the experts know what to do. This quadrant demands speed - but the speed is practiced.

Adaptive Challenge (deliberate speed, high uncertainty): Complex problems with no clear answer - where learning, collaboration, and experimentation are essential. Think transforming culture, redesigning service delivery, or long-term climate adaptation.

The Fog Zone (high urgency, high uncertainty): The hardest quadrant. The stakes are high, but the path is unclear. Time is short. Mistakes are costly. And waiting too long can make things worse.

When Training Meets Reality

I’ve worked in conflict zones and was on the ground in Baghdad’s Green Zone when missiles flew overhead with such regularity they became routine. I’ve developed heavy-duty shock absorbers and can usually stay focused in high-stress environments.

But when my five-year-old son began hallucinating from a sudden high fever, I panicked. I called an ambulance, and the paramedics took over - efficient, calm, practiced. They started with a cold bath. They knew what to do. I didn’t.

That’s the difference between an expert response and a fog zone moment.

In the fog zone, it’s not just the pressure - it’s the ambiguity. There’s no playbook, no proven fix. It’s where many leaders freeze or misstep. And unless we’ve trained for it, we’ll likely do the same.

The Training We Rarely Provide

Firefighters don’t stay calm in burning buildings because they’re fearless. They stay calm because they’ve practiced. They suit up and train in purpose-built structures set on fire for that reason. They learn to read heat, manage adrenaline, and act fast - without losing their head.

We rarely give leaders the same kind of purposeful preparation. But we should.

I believe in training leaders not just to analyze systems, but to feel their way through them. Diagnostic skill is vital - but so is embodied readiness: the ability to stay grounded in your own nervous system, even when the system around you is in turmoil.

That means developing:

System sensing: Quickly reading a room, identifying hidden dynamics, separating panic from productive urgency.

Embodied practice: Training not just the intellect, but the body - so that under pressure, leaders can stay calm, curious, and present.

Emotional regulation: So that even when the leader feels uncertain, they can still create steadiness for others.

The New Curriculum

At Columbia SIPA, as we redesign our core leadership course, we are explicitly preparing students for this fog zone quadrant, using the Leadership Challenge Map. We’re building simulations that expose students to ambiguity and tangible consequences because we want our graduates to be able to:

- Diagnose whether a challenge is expert response, expert delivery, adaptive, or fog zone

- Make decisions in real time under crisis conditions

- Stabilize teams through confusion and fear

- Lead with courage that doesn’t pretend to have all the answers - just the clarity to move forward anyway

When the Fog Descends

The next major leadership challenge won’t always look like a mine collapse. It might come as a data breach, a key resignation, a reputational storm, or a sudden policy failure.

What it will share:

- No obvious solution

- High visibility or consequence

- A narrow window to act before things spiral

In our curriculum, we introduce practical tools to support leadership in these moments. One of them is the Fog Filter - a simple, situational decision tool that helps leaders assess whether to act, pause, or probe when time is short and clarity is missing. It doesn’t offer perfect answers. But it offers disciplined motion - a way to move with intent when direction dissolves.

Leadership in the fog zone isn’t about clarity - it’s about creating direction when none exists. It’s about staying steady when others shake. About making the next best move - even when you can’t see the destination.

The fog zone is where leadership is tested. And the time to train for it is now.